spaces(in)BETWEEN shares the chosen walking routes of a sociologist, an artist and a musician, and the body of work they have produced in relation to these. The project also involves a collaboration with film-maker Duncan Whitley, who produced three short films capturing a glimpse into their processes.

This project was co-comissioned by THE POD and Coventry City of Culture Trust for Green Futures, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Severn Trent Community Fund.

An Editorial, Of Sorts

by Alix Villanueva

by Alix Villanueva

Spaces in between. What are they, and perhaps just as importantly, where can they be encountered? Suggestive of an emptiness, a non-entity, they none-the-less maintain the form and structure of all that is there. In the caseroom, the typist picks up thin, lead rectangles and wedges them in between words. When the page is printed, they do not appear on the paper.

Yetwithoutthemtherewouldbenowordsorsentences.

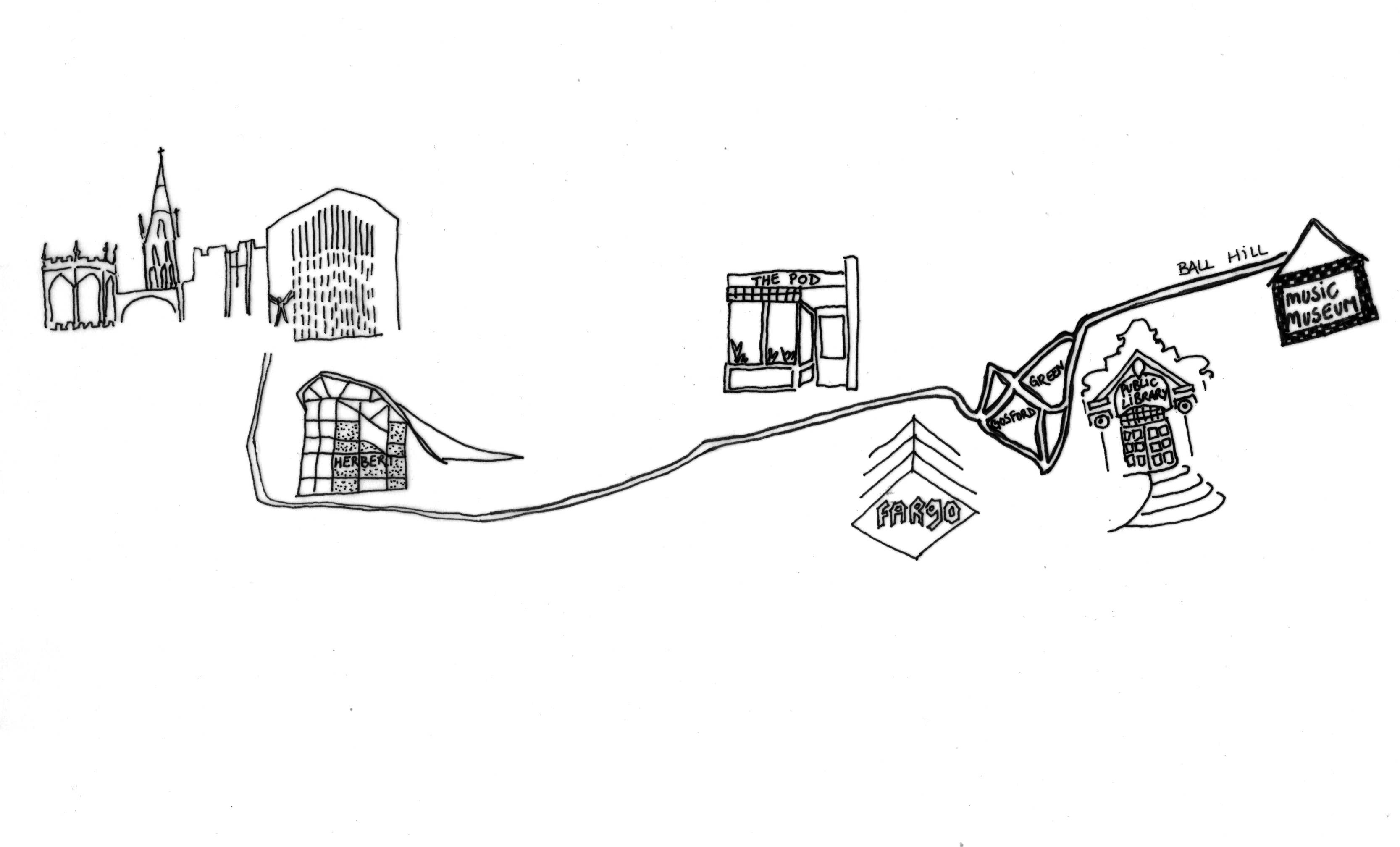

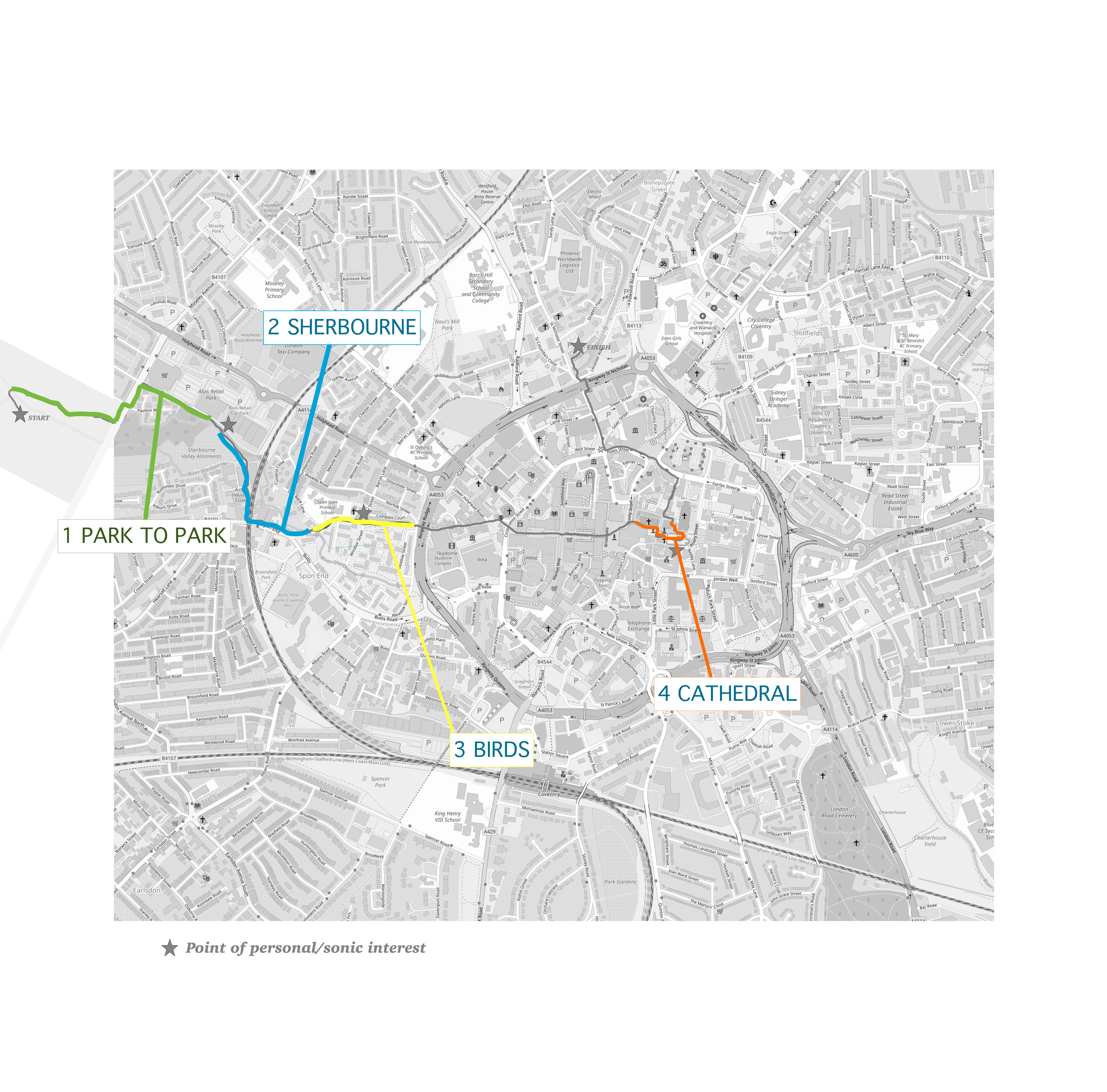

We asked a musician, an artist and a sociologist to take us to their spaces-in-between. What emerged were three distinct walks, spanning the west of Coventry in Spon End, through to Ball Hill and as far east as the suburb of Wyken. Though unique in character, the three walks bear similarities in the way in which memory has provided direction to their feet. During the end of April, forensic botanist Mark Spencer, film-maker Duncan Whitley and I were taken on the three walks.

* * *

On the 26th of April, and westernmost, Charlie Tophill meets us at Lake View Park. She is a musician and tells us she grew up by the seaside, moving to Coventry only a few years ago. Her pull towards water in a city very much lacking in water takes us along the River Sherbourne through Spon End and to the Cathedral. Through Mark Spencer, we learn about the plants that grow along the path, about the barely noticeable but scientifically significant Thale Cress, about the asexuality of Dandelions, about the presence of Midlands Hawthorn indicating ancient woodlands and the alelopathy of Garlic Mustard.

We walk over the culverted parts of the river, discussing the ways in which the man-made hard margins of the riverbed make the water run faster and lower its resistance to flooding. To make a river more stable, we have to slow the water flow and, with sufficient light and access to soil, bankside plants would be able to serve this purpose.

Upon reaching the Arches we begin to look up at the plants growing vertically, their roots firmly embedded in the rocky walls. We spot Maidenhair and Rue-leaved Spleenwort, which dislike pollution and were almost wiped out with the rise of industrialisation but came back after the introduction of the Clean Air Act. There is so much Buddleia, firmly encroaching onto the hard surfaces. A rarer specimen of Pellitory of the Wall makes itself known to us. These are all plants that have adapted to the hardscapes of our cities, much like pigeons have adapted from cliff-edges to building façades.

Looking at spires of Rosebay Willowherb, not yet in flower, Mark Spencer tells us about its other names, one of which is Bombsite Weed (and interestingly enough, Bombsite Bush is another name for the invasive Buddleia). Rosebay Willowherb did particularly well after the wars, as explosions carried its parachuting seedheads that then settled down on the bared ground and took little time to thrive. We learn that bombsites are a genre of brownfield site, of particular ecological interest. Tophill went on to adopt the name Brownfield for her EP which emerged from her work for spaces(in)BETWEEN.

The four sonic works she has produced are composed using an orchestra made up entirely of sounds collected from different points on her walk. We are transported across four distinct segments she calls ‘scenes’, a term suggestive of interaction and action rather than static passivity. In these scenes, different beings and elements are subtly referenced and come to merge, the running of water, the birdsongs, and the fragments of dialogue, all coming together with the rhythmic use of the instruments she built from her field recordings.

The last scene, entitled Cathedral, is the only one where we hear Tophill’s vocals. The song is full of precise details encountered from within the body of the Cathedral. On her note-taking as part of her song-writing process, Tophill tells me: “I approached note-taking more like a survey than a diary entry, which I would have normally done. I made notes of what I observed and heard. […] The whole process was not led by autobiography, only by presence in the space.”

The film produced by Duncan Whitley on Tophill’s work gives us a glimpse of her use of note-taking and drawing, as well as the physical interactions she has with her direct environment from which she built her sound library. In a muted palette, characteristic of Whitley’s work, a wooden mallet and a drumstick, are witnessed extricating sounds from things evoking a semi-urbanity: an open pipe, a wooden pole to which is attached rusty barbed wire, emerging out of the out-of-focus green of the plants that give context to her walk.

In one particularly visually striking fragment, Tophill’s hand is seen rhythmically grabbing a chain, suggestive of the relationship between the use of her body, encountered objects and her environment in her musical process.

* * *

The next day, sociologist and writer Dr Nirmal Puwar takes us on her walk across Ball Hill. The walk is short, but packed with personal, social and civic references for Puwar. We set off from the 2 Tone Café on Walsgrave Road. She points out the displays of our consumer relationship to food through the copious amounts of fast food places that surround us. Across the road is an abandoned shop front with a blue façade – a Boots that closed down. ‘For Sale’ boards are visible all along the side streets.

We pass by a series of small front gardens, almost all un-kept, some strewn with litter, others recently sprayed with glyphosate. Litter is something familiar to Puwar, having written “Walking Through Litter”, in which she describes the litter that now paves the same walk she writes about for spaces(in)BETWEEN.

Peering into these small front gardens, Mark Spencer starts pointing out the species that grow in them. According to him, these gardens are filled with evidence of certain kinds of human actions and decisions: Buddleia, an import from China; Oxford Ragwort, originally from Mount Etna and brought to the Oxford Botanic Garden where it eventually escaped, got onto the railway and was spread by train travel; Yellow Corydalis, a garden escapee from the foothills of the Alps; Sycamore, which went extinct here in the last ice age but was reintroduced around the Norman period. He also points out the native plants: Bracken, Herb Robert, Sow Thistle, Dock. These he calls the ‘survivors’, those who made it past the agricultural periods and have found a small surviving niche in our urban areas. There are resonances with themes that are integral to Puwar’s writing, unpacking experiences of diaspora and identity as evidenced in “Indomitable Mint”.

In one of the gardens, growing just along the side of the wall marking the start of the pavement, the white clusters of Snow-in-Summer, Cerastium tomentosum in its Latin name, catch our eye. These were in fashion in the mid 20th century in working-class gardens. This plant appears in Puwar’s writing, its name evoking the memory of the tragic loss of her brother from within the walls of the Walsgrave hospital as snow uncharacteristically blanketed the ground in April.

We walk past the Stoke Library and sense the ghost of the filled-in swimming pool below our feet. Above ground, Mark Spencer points out the clear evidence of glyphosate application. The yellowing corpses of Chickweed, Dead Nettles and other specimens of plants that grew between the cracks in the pavement tell us a story. Amongst them, Docks endure. Improper applications of herbicide breed resistance. We are indignant witnesses to human malpractices.

Full of academic and conceptual references, and yet moving and accessible, Puwar’s address to her deceased mother deftly weaves the intimate with the civic and social, through different layers of temporality and power structures. As part of her writing process, Puwar undertakes segments of her one-mile walk with different companions: botanists, artists, activists, scientists, local residents, non-humans and ghosts. These become lenses through which she reads the details of her walk, her attention being drawn to novel things that have been there all along.

“Ball Hill”, the film Duncan Whitley produced with Nirmal Puwar, gives us a glimpse into one such layer. Detailed, almost surgical views of Puwar’s hands holding up plant specimens gathered and identified from her walk with Mark Spencer roll on the screen. We would almost believe they were photographs, were it not for the subtle tremble of the hand yielding to the effort of keeping still, a subtle reminder of our living, breathing bodies juxtaposed with the herbarium-like presentations of plants against a white background. Layered on the top, we hear Puwar address her mother, with the last line of her text read in Punjabi, the language she would have communicated with her in.

* * *

The last walk took place a couple of days later, although without Mark Spencer present as he got called in to a forensic emergency. Still, Duncan Whitley and I had the pleasure of an intimate non-walk (due to its non-linear nature) through the suburb of Wyken, in east Coventry. The suburb’s layout is characterised by 196 alley gates guarding what Coventrians call “entries”, these back alleys of housing estates built pre-war around the 1930s, which were wide enough to accommodate carriages and cars but just a little too small for today’s vehicles. Green’s childhood and teenage memories of the geographical layout of his neighbourhood are suffused with places we can no longer access. Short routes often meant cutting through the then-opened backstreets and, as we walk, memories surface of ball games, or of being shouted at by a neighbour for cutting through where one was not supposed to be. These entries bear no formal names. The neighbourhood itself is anchored in a misnaming, coming up on maps as Church End, a name that has never been uttered on local lips. Green takes it upon himself to create associative names for the entries, based on specific autobiographical memories.

The walk is not linear either. Often times, we have to turn back upon ourselves. “You can now only assess a street by its façade. You can no longer see the back,” Green tells us. This is apparent in Green’s post-it paintings, in which the backs of his drawings gain just as much significance as the fronts do. Led by the dots that have bled through the page from the front, Green maps out the lay of the land, something he tells us his feet have always felt beneath the hopscotch layout of the pavement slabs that characterise this suburb. The slight incline of Morris Avenue now lined with identical houses can be felt by the feet of the attentive walker. Broken sightlines can only be glimpsed through the gates of these entries and one can almost imagine what the land might have looked like when it was still farmland. There are no trees here. In the summer, the heat pools along the paved slabs.

As we walk, Green often bends down to pick up discarded objects. A category of object that seems to come up time and again is the bright coloured disposable vape canister. Green puts these in his pockets as he walks along with us. The ground is littered with them. Once back in the studio, he will flatten and dissect them, his fingers tainted by the artificial smell of watermelon, candyfloss, or whatever other flavour these come in. He is interested in addiction, as has been exemplified in the past work he has done with encountered nitrous oxide canisters, “especially in a place where nothing happens” Green tells me.

“The place I used to live in is a barren void,” says Green. Barren of resources and infrastructure, a neighbourhood dubbed by Green as “Fortress Wyken” in which gates, surveillance cameras and anti-climb paint are the norm. I stick my hand into the thick greasy black mess at the top of a gate before Green is able to warn me. He shakes his head, a smile on the corner of his lips.

In a palette that echoes that of the corpus of post-it paintings produced by Green, Duncan Whitley’s film, “(in)secure Childhood”, captures the works in their context. The works of art are returned to their place of conception, deposited on the gates of the entries or by the brick walls that they reference. This gives the viewers a glimpse into the final stage of Green’s process, which would involve the placement of these works back into the entries out of which they were coaxed. This is a challenge for the artist, who feels uneasy engaging in activities that are not considered normal for that area. The authority afforded by the camera lens made the filming possible, but not without glances and questions. The slow cadence of the film is interrupted by the final segments of the film, in which the field of focus is expanded to beyond the entry gates and into the sightlines that they keep concealed, evoking a longing for a walk down the forbidden paths.