In the novel ‘Here is where we meet’, based in Lisbon, John Berger observes the outline of a female figure walking towards him. As she becomes closer and comes into focus, he notices it is his mother and she has been dead fifteen years. She states that the dead don’t stay where we want them to. So often we walk with ghosts; our mind roams with time as we ramble with our feet in the here and now.

We are mangled time-machines; envisioning futures with distant pasts, seeking repair when we are broken.

rubble along Ball Hill

The lines on the hand curled over, held along journeys, from crawling to the handlebars, in between the laughter of wheeling down the hill of Ball Hill. The paths are now wheelie binned all over; discarded nappies, polystyrene take-away boxes, strewn on asphalt pathways. The purple ivy-leaved toadflax, a rock climber from Italy, has made a home in the crevices of cracked urban walls, with edible flowers, which we don’t eat. Purple hanging buddleia, introduced from China to the UK in the 1890s for gardens, invites dances with butterflies, the wind spreads their seeds far and wide, making them commonplace in urban wastelands. In between the infrastructural lines of migration and colonialism, plants, people and animals have co-mingled.

Oh what a ball we had, as we whizzed down Ball Hill with the rain in front of us, you holding your arched umbrella majestically mid-air, while I drove the wheels of what you referred to as my gaddhi (motor vehicle), since I didn’t drive, in this motor proud clogged city. The pavement almost clear all the way then, looking out for dog poo or potholes that could jerk us (you) off course. Laughing at the hilarity of times, when on the same path, a bright yellow block heel had clopped off a yellow strapped sandal, bought in a job lot from Curtiss’s by the young women in the neighbourly circles, putting the elegant jaunt, of the bell bottom wearer, out of keel. Forming part of your own helter skelter of life between Coventry and the diaspora of oceans you crossed to be here.

***

Threaded through the time of now, deep time, the personal, colonialism and migration of plants, soil, animals, human and non-human life, a key note in the writing comes from observing how places and life are simultaneously both

decomposing and recomposing.

As we compose academic prose for the world, Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer can enable us to do a different braid with our writing; in terms of genres, disciplines and vernaculars.

This walk has become a braided form of writing through several elements:

1. This walk is multi-scalar, it moves from micro details to large historical changes, from personal intimate biographies, to structural global phenomena.

2. It is not an isolated walk, as it is linked to other places, through infrastructures, networks of relations and power structures.

3.

This walk moves back and forth in time, it is an atlas of emotions with layered temporalities. It engages in a hybrid mode of contemplation. Reflecting as a daughter and sociologist who returns ‘home’ and finds herself becoming writer-as-resident.

4. It is based on a one mile walked alongside others, including botanists, artists, activists, residents, the non-human and ghosts. Each of these companions inflect how one walks, what is observed and imagined, becoming ‘companion thinkers’, as Isabelle Stengers puts it.

***

Three-foot tall perimeter walls hem in the soil of sloping gardens, meeting my eye level, as I walk down the hill, counting To Let signs which have sprung up in abundance. Above and away from the path sit Victorian houses, chopped into multiple HMO occupation properties for maximum rent, the cash rolling in with no civic accountability for the maintenance of infrastructures. Mattresses, ripped bin bags and pushchairs discarded amongst the nettles, soothing dock leaves co-exist. From rock faces, ivy-leaved toadflax adapts to growing in built urban environments, finding spaces in between glass and decomposing food waste to crawl up the steep stairs to the houses.

In the 1970s, in your fifties, you abundantly pushed a full size bouncy spring suspended pram, with your strong petite 5ft frame, up Ball Hill, with your elder two grandsons in it, while my hand held on to the side bar and we admired the carefully planted front gardens. Gardens can be a gift to neighbours and bypassers. Then, we certainly chose to walk up towards Ball Hill so we could lift our heads to take in the careful curation and changing colours of what was planted on the side of the sidewalk. Your smiles drifted away from us, aided by small drops of morphine, as one of your loyal grandsons held on to your grip to the end. They placed precious you in a bag and took you to the morgue where your body was refrigerated as it tried to decompose. The walks stay with us, as we walk the paths we took both decompose and recompose.

Nirmal visiting one of the gardens that still looks maintained along Ball Hill

Front gardens we pass are integrally related to a multiplicity of global routes, through the production of discarded plastics, the exportation of waste and a pluriverse of plant journeys. The green and shimmering purple of Briza maxima, also known as great quaking grass or pearl grass, quivering grass, shaky grass and shell grass from North Africa and the Mediterranean, delicately dangles over plastic bottles and tin cans, a misnomer to be logged with the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland, says the botanist Mark Spencer, as it has become naturalised in the far south of the UK and now seems to be moving north. Used as an ornamental dried flower, quivering grass is now classified as an invasive species that has become a common weed of waste places, considered to be threatening native species of plants and crops in countries as far as Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Hawaii, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala and Honduras. Diasporas of seedlings and cuttings have travelled by the designs of trade and movement across the globe, as well as through unwitting processes of migration from non-human lives. The spores of moss, one of the earliest plants to grow on land, is limited to spreading laterally. In between the spaces of the feathers of birds, this plant, like others, has dispersed to all parts of the world.

plants collected on the walk

image by Duncan Whitley, labels by Alix Villanueva

The taxonomic language of botany is replete with references to migration, native, non-native, invading, naturalised, escaped, adapted, extinct and survivors, with an emphasis on geographical location, ecologies and changing value systems. For diasporic human lives these words are irksome, inviting vigilance. In their late eighties, with their walking sticks in hand, both my mother and father were naturalised as British citizens, this was after they had lived in the country for over fifty years. They were handed citizenship certificates by a Muslim South Asian Lord mayor at a ceremony held at Coventry council house, where the national anthem played on a CD player, and a portrait of the queen stood centre staged on an easel. We pass the Day lily, also known as Wayside Burma Comforter, treated as an ornamental plant in the UK, but a food item in East Asia. It may have sat beside my father when as a young man in WW2, under British colonial rule, he fought against the Japanese, while some of the prisoners of war from British-Indian switched to fighting alongside Japan under Rash Behari Bose. And you my mother sung ‘Oh Letter from Burma’, with the women left in wait at the home front in India of the dreaded news from the Burma war front. As the wind speaks through the comforter, I can hear those longing tones, however distant your voice has become with time. These and other boliyan you carried with you to dance giddha in the making of home in a cold British climate that you warmed to too.

***

How I approach what is decomposing and recomposing is very much informed and affected by

who I walk along with.

This could be ghosts, my young daughter, a local resident, activist, or soil scientists, as we took the path last week with Maria Puig de la Bellacasa and photographer and artist Adele M Reed. Or a botanist; organised by the POD and Food Union, with the ecological writer Alix Villanueva, a few weeks ago.

Strolling and stopping is composed by who you walk alongside. A 5 min walk became a 2 hr walk with the botanist, as it did with the soil scientists, who pointed out the thousands of years it would take for the plastic littered amongst the wild plants in the front gardens to bio-degrade. They point out there is a lot of metal in the soil, especially silver in Coventry. We discuss how soil memory is constituted, with the industrial heritage of the motor car.

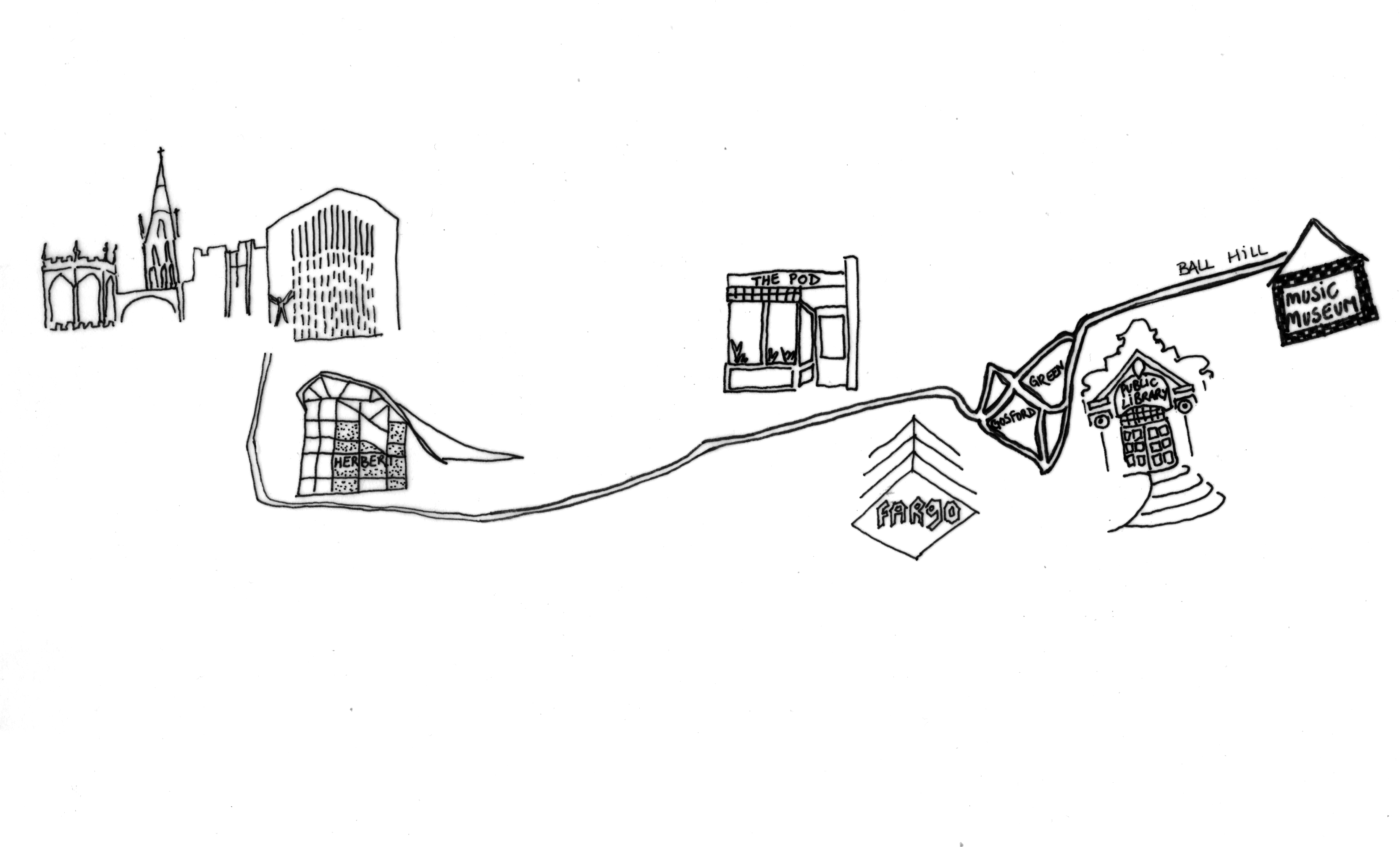

There are particular stops on the way, including gardens where decay and new life come together in Ball Hill. The stop of home, the Stoke library, the covered mens toilets, the filled in swimming pool, the wilderness of the disused railway and the struggle for an orchard, the park in the middle of the cuts of highway, made for the motor city, the public-private partnership of Fargo the creative quarter, where tyres were sold, by Harrabin Construction, who have the business fingers all over the town, the making of Common Ground cafe, the soil to table philosophy of the POD, the rise of student housing, the destruction of protected trees, the hope for civic creativity in the Herbert gallery and Coventry cathedral.

***

Snow-in-Summer, clumps of white flowers carpet gravel gardens and hang off the perimeters of walls. The juxtaposition of snow-in-summer takes me to 9th April over 20 years ago when your dear eldest son, Harbans, who was such a gift to you when you birthed him years after you entered the marital home that had begun to deride you as a barren beauty of a woman. The snow fell thick in April, as his last breaths were taken away from him, high up in the towers of the half inept Walsgrave hospital. The world fell inside out on you, and us. The two shades of yellow of daffodils circled the centre of the roundabout as we sat in cars on the way home. That time of daffodils stays with us. The words from school books read out aloud resound ‘April the cruellest month of all’ from TS Elliot’s The Waste Land, a text we poured over as literature students with Mrs Ranson:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire…

As we sat at Birmingham Airport waiting for our flight to India, to take my brothers ashes to the rivers of Kiratpur in Punjab, our mother moved her hands gently over the copper coloured urn with my brothers ashes in. She then rubbed her hands on her face.

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire…

As we sat at Birmingham Airport waiting for our flight to India, to take my brothers ashes to the rivers of Kiratpur in Punjab, our mother moved her hands gently over the copper coloured urn with my brothers ashes in. She then rubbed her hands on her face.

***

The Punjabi folk song ‘Mitti De Bawa’, was sung by a young woman longing to be a mother, her husband is on his travels, possibly at war. She makes a doll of clay as an imaginary child. Feelings of jealousy towards other women are also acknowledged in the lyrics. There are several versions of it. It has been sung famously by the duo Chitra and Jagjit Singh.

Mitti Da Bawa (doll made of soil)

Mitti da main bawa banani aan,

ve jhagga paani aan,

ve utte deni aan khesi,

So ja mitti diaa baawiaa,

ve tera pio pardesi

Mitti da bawa nahion bolda,

nahion chaalda ,

naan hi denda e hungaara,

Na ro mitti deaa baawiaa,

ve tera pio vanjaara

Kade taan main launi aan tahliaan,

ve pattaan vaaleean,

ve mera patla maahi,

Kade launi aan shahtoot,

ve tainu samajh na aave

Mere jehiaan lakhkh goriaan,

ve tanee doriaan,

haye godee baal hindole,

Hass hass dendiaan loreeaan,

haae mere ladan sapole

Mitti da main bawa banani aan,

ve jhagga paani aan,

ve utte deni aan khesi,

So ja mitti diaa baawiaa,

ve tera pio pardesi

Mitti da bawa nahion bolda,

nahion chaalda ,

naan hi denda e hungaara,

Na ro mitti deaa baawiaa,

ve tera pio vanjaara

Kade taan main launi aan tahliaan,

ve pattaan vaaleean,

ve mera patla maahi,

Kade launi aan shahtoot,

ve tainu samajh na aave

Mere jehiaan lakhkh goriaan,

ve tanee doriaan,

haye godee baal hindole,

Hass hass dendiaan loreeaan,

haae mere ladan sapole

I craft a doll from soil,

make it wear a little shirt,

cover it with a blanket…

Go to sleep my doll of soil,

your dad is abroad…

My doll of soil does not speak,

does not walk,

does not call to me..

Don’t cry my little clay doll,

your dad is a wanderer…

I planted sheesham trees,

they grew lovely leaves,

aah my scrawny beloved…

I planted trees of mulberry,

why don’t you respond…

The other women of the town,

as pretty as me,

have kids in their lap..

Sing them lullabies,

and my soul is a snake’s playground

I craft a doll from soil,

make it wear a little shirt,

cover it with a blanket…

Go to sleep my doll of soil,

your dad is abroad…

My doll of soil does not speak,

does not walk,

does not call to me..

Don’t cry my little clay doll,

your dad is a wanderer…

I planted sheesham trees,

they grew lovely leaves,

aah my scrawny beloved…

I planted trees of mulberry,

why don’t you respond…

The other women of the town,

as pretty as me,

have kids in their lap..

Sing them lullabies,

and my soul is a snake’s playground

***

Our Mother at Blackpool

The frothy waves come and go, lashing through the pebbles, taking more of her away.

Joining her specs of dust with grains of grey sand. Curling and enfolding her into the vast unending oceans of the seas.

We have our thick coats on, it is cold.

The sun shines on us as we finally let her go, at 11am on 15 February 2020, not far from the northern pier.

We are bent over. We are silent together and alone.

We keep looking back at her, while we walk away.

***

click on the bookstack to download Nirmal’s reading list

***

Alix Villanueva interviews Nirmal Puwar on the work she did for spaces(in)BETWEEN