AUTUMN

Events and Publications

October 2019, Apples

Ceilidh at CV5 Community Allotment with Alix Villanueva

Apple Day Wassail at CV5 Community Allotment with Camilla Nelson

November 2019, Gardens

Screening of ‘A Garden Phenomenology’+ Q&A at CCCA Shed with Alix Villanueva

‘A Garden Phenomenology Supper Club’ at POD Cafe with Alix Villanueva

October 2020, Apples and Dew

Publication and distribution of Apples and Dew with Yva Jung

Critical Plant Walk at CV5 Community Allotment with Mark Spencer

November 2020, Becoming

Publication and distribution of Becoming artist book series with Camilla Nelson

Apple Day Wassail

Camilla Nelson October 2019

images 1, 2, 3, 4 by Alan Van Wigerden

images 5, 6 by Adele M Reed

Camilla Nelson’s work can be accessed through

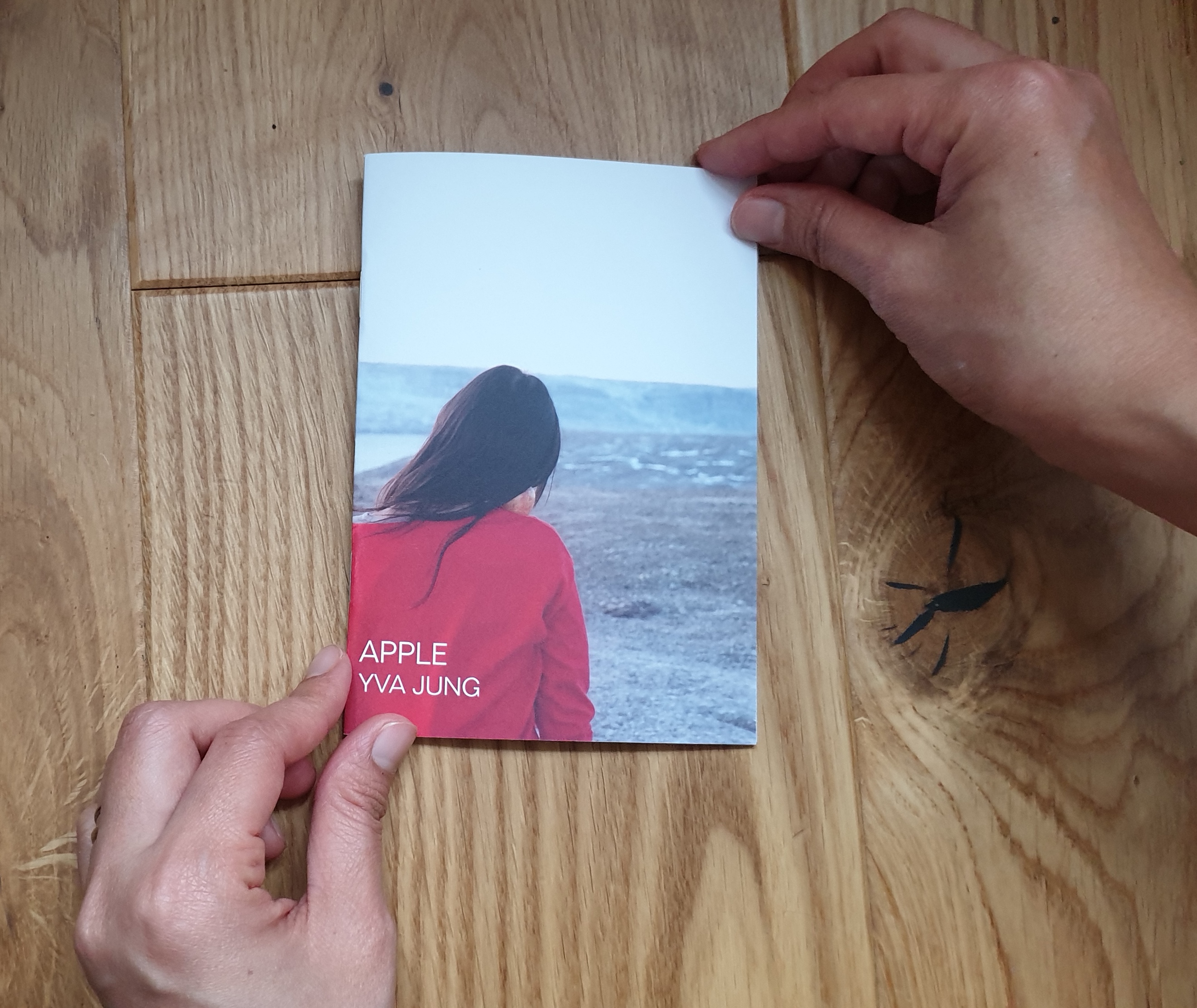

Apple

day was "launched in 1990 by Common Ground. The aspiration was to create a

calendar custom, an autumn holiday. From the start, Apple Day was intended to

be both a celebration and a demonstration of the variety we are in danger of

losing, not simply in apples, but in the richness and diversity of landscape,

ecology and culture too."

For Apple Day at the POD’s CV5 Allotment, language artist Camilla Nelson delivered a live, improvised a live, poetic response to an apple tree - reading the tree with all the senses and letting the sensations of this being-with-tree flow out in words. This way of performing with trees grows out of Camilla's practice-based research in 'Reading and Writing with a Tree: Practising "Nature Writing" as Enquiry' (Dartington/Falmouth, 2012).

For Apple Day at the POD’s CV5 Allotment, language artist Camilla Nelson delivered a live, improvised a live, poetic response to an apple tree - reading the tree with all the senses and letting the sensations of this being-with-tree flow out in words. This way of performing with trees grows out of Camilla's practice-based research in 'Reading and Writing with a Tree: Practising "Nature Writing" as Enquiry' (Dartington/Falmouth, 2012).

This inaugural event, which launched the underGROWTH programme, introduced some our residents including Nellie Cole, Kirsten Norrie and Iain MacKinnon. underGROWTH organisers Lauren Sheerman and George Ttooli joined in with an improvised call and response from Lauren’s book about folklore.

‘A Garden Phenomenology’ Screening and Supper Club

Alix Villanueva

November 2019

November 2019

image of dinner by Izzie Grove,

images of screening by Lauren Sheerman,

still from film

Alix Villanueva’s work can be found on: https://alixvillanueva.com/

‘A Garden Phenomenology’ is a film by Alix Villanueva created for the Coventry Biennial and for underGROWTH. It was produced after a series of micro-residencies spent at the POD’s CV5 community garden. It considers ways in which our bodies are the primary point of contact with the world around us, by going through each of the five senses. This work, informed by the medieval tapestries “La Dame à la Licorne”, also investigates a possible sixth sense through the poetry of the garden, the insistence of ritual, and a different way of letting things grow. The film was premiered in the CCCA Shed in Fargo Village.

The film can be viewed here: https://vimeo.com/380104504

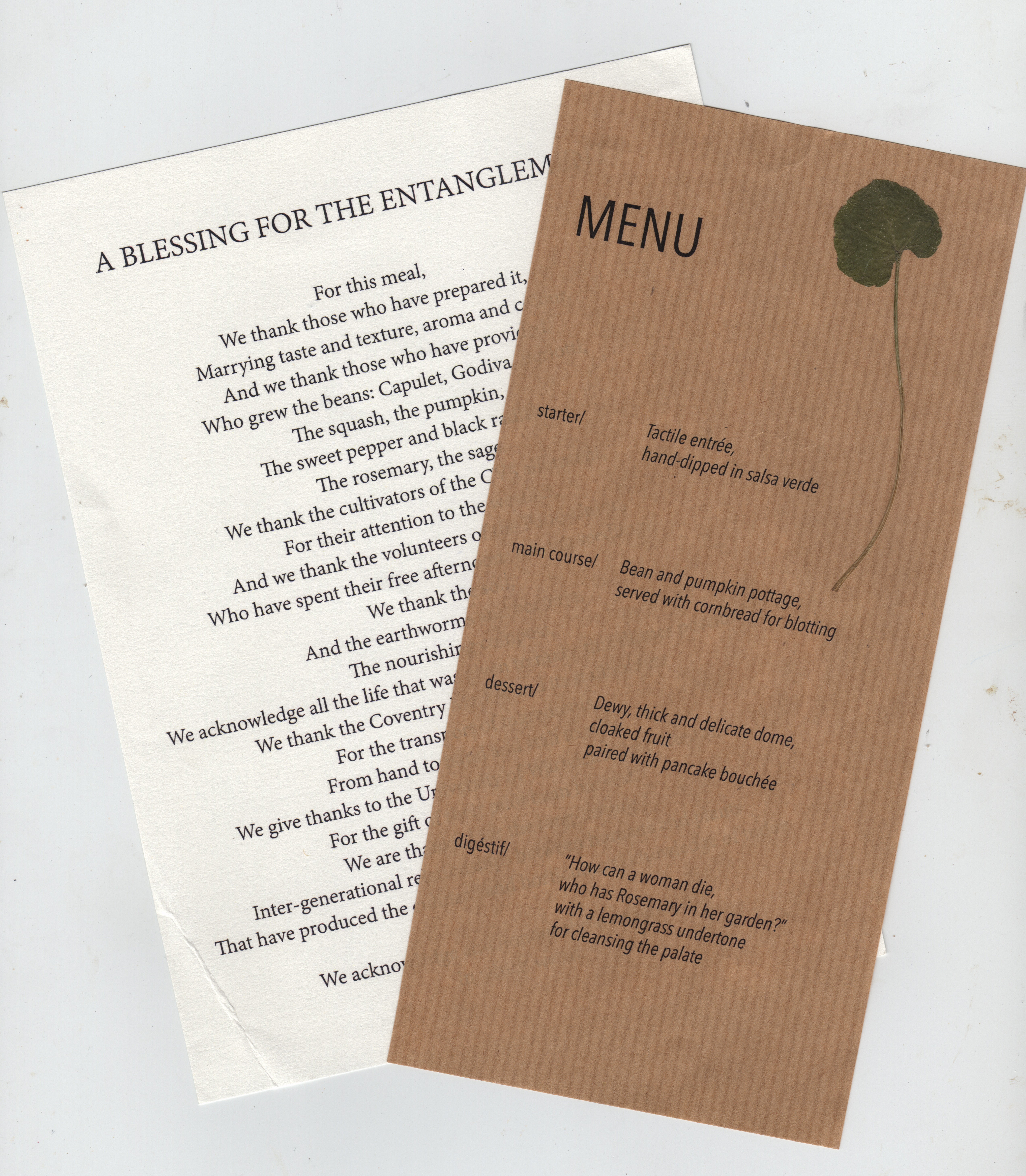

As a sister event, Alix Villanueva helped put together a Supper Club at the POD cafe, along with Tom Simkins, Izzie Grove, Greg Muldoon, Matt Rheeston and Rosie Bolton. Using medieval ritual as well as sensorial enhancement and deprivation throughout the dinner, Alix brought the participants back into the film’s strange atmosphere. The menu, curated by Tom Simkins, featured bean and pumpkin pottage, a rosemary and lemongrass digestif, and raindrop cakes. A majority of the ingredients were grown on the CV5 alloment site. A specific soundtrack was also put together by composer and sound designer Paul Koutselos, which incorporated bird call and sounds from the compost.

The film can be viewed here: https://vimeo.com/380104504

As a sister event, Alix Villanueva helped put together a Supper Club at the POD cafe, along with Tom Simkins, Izzie Grove, Greg Muldoon, Matt Rheeston and Rosie Bolton. Using medieval ritual as well as sensorial enhancement and deprivation throughout the dinner, Alix brought the participants back into the film’s strange atmosphere. The menu, curated by Tom Simkins, featured bean and pumpkin pottage, a rosemary and lemongrass digestif, and raindrop cakes. A majority of the ingredients were grown on the CV5 alloment site. A specific soundtrack was also put together by composer and sound designer Paul Koutselos, which incorporated bird call and sounds from the compost.

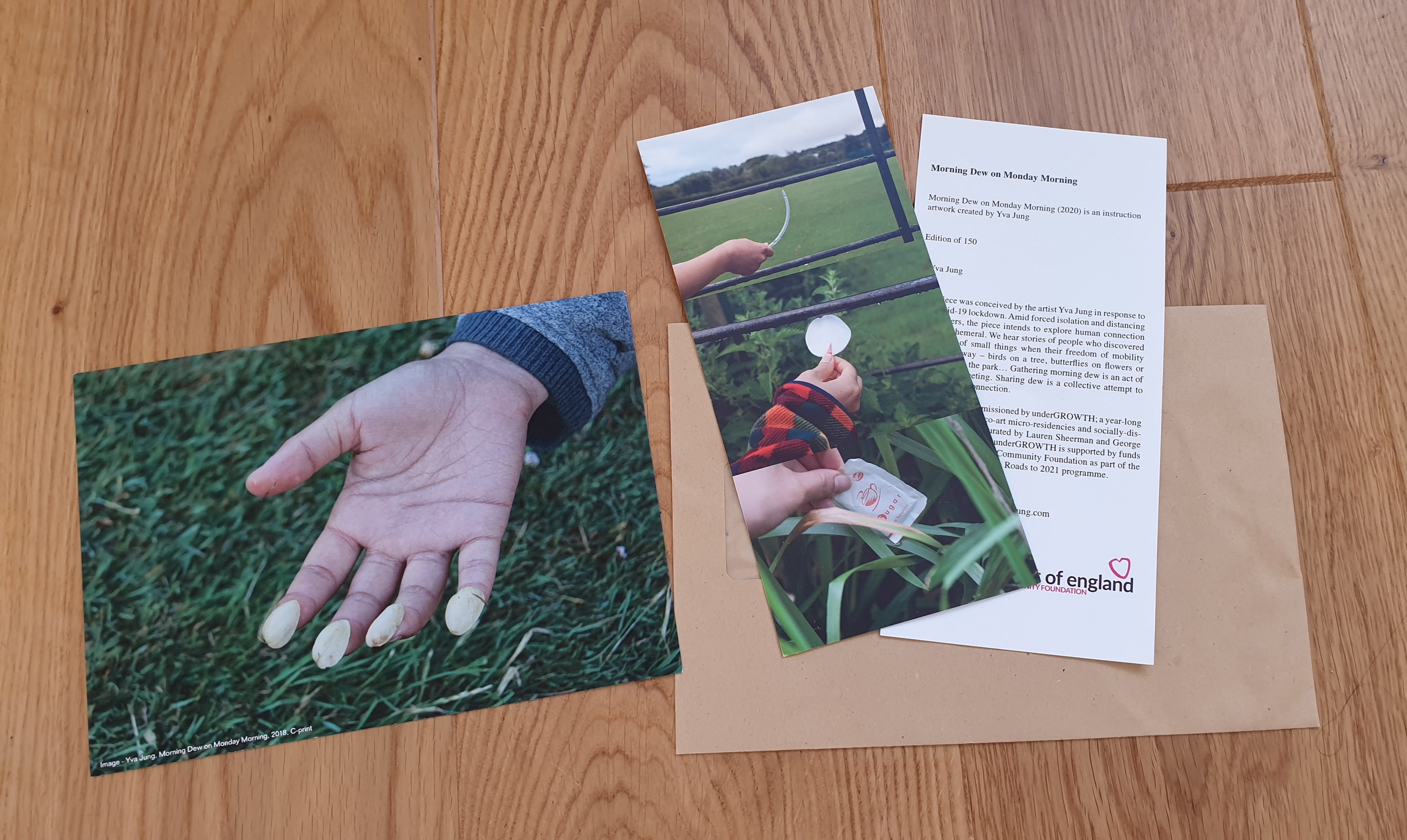

Apple and Dew Zines

Yva Jung

October 2020

October 2020

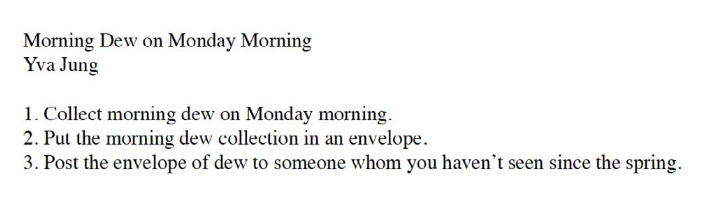

Yva Jung’s micro-residency with underGROWTH was interrupted by the lockdown. She connected with the followers of our project through postal offerings of a zine and an invitation to collect dew on a Monday morning to send to someone close (see instructions above).

Download Yva’s digital zine here.

Critical Plant Walk @CV5

Mark Spencer

October 2020

4 mini essays

October 2020

4 mini essays

1. Our allotments are part of nature. They are full of wildlife;

some of this wildlife we grumble about and call weeds. Yet weeds are an important

part of allotment life. Many of these plants are vital food sources for

insects. In early spring, the attractive plum-red, purple, and white flowers of

dead-nettles (known as Lamium to us botanists) produce abundant nectar.

There are 248 different dandelions (Taraxacum) in Britain and Ireland.

Some of them are very rare and restricted to special habitats such as the tops

of Scottish mountains or the fens of East Anglia. Other types of dandelion are

common roadside and garden inhabitants. Do not aim

to eradicate these joyous wonders, they too support many types of insect. On my

own allotment, I allow patches of wild plants to flourish amongst the

vegetables. Common speedwell (Veronica persica), scarlet pimpernel (Lysimachia

arvensis) and the tiny snap-dragon relative, sharp-leaved fluellen (Kickxia

elatine) pepper the ground with dashes of blue, red, and yellow. These low

growing plants provide food and shelter for insects and help reduce water loss.

Fighting a never ending war with wild plants in your garden is exhausting, so embrace

them and use them. Some can be eaten, common plants like chickweed (Stellaria

media) and fat-hen (Chenopodium album) are nutritious and can be

used like spinach. Nearly all can be used as a green mulch and dug in when the

time is right.

2. Some plants are invasive and can cause environmental damage. Scientists try to be very careful about describing a plant as invasive. An invasive plant is one that has the potential to damage or destroy habitats (such as ancient woodland, grassland, or ponds) or threaten other plants or animals with extinction. Most of the escapees from our gardens and allotments are not of serious concern, but some are. The delightful sugary pink flowers of Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) are now a common sight along many riverbanks. Sadly, these beautiful plants are causing serious harm. Despite its reputation as a source of nectar for honeybees, scientific studies of this plant have shown that it causes declines in riverside plant and insect diversity. This rapidly growing annual plant also outcompetes other plants. Each autumn Himalayan balsam dies back leaving riverbanks bare in winter. Bare riverside soil is much more vulnerable to erosion after heavy rain, and the washed away soil causes major damage downstream and kills wildlife. We can all play our part to reduce the spread of invasive species:

· Never throw away garden waste in the countryside – compost and recycle.

· Do not plant spare garden plants along roadsides or nearby woods, as this can spread invasive plants and damage or destroy what is already there.

· Always compost excess oxygenating plants from your pond and do not put them in a pond nearby. Many oxygenating aquatic plants are highly invasive and may spread pests and diseases.

2. Some plants are invasive and can cause environmental damage. Scientists try to be very careful about describing a plant as invasive. An invasive plant is one that has the potential to damage or destroy habitats (such as ancient woodland, grassland, or ponds) or threaten other plants or animals with extinction. Most of the escapees from our gardens and allotments are not of serious concern, but some are. The delightful sugary pink flowers of Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) are now a common sight along many riverbanks. Sadly, these beautiful plants are causing serious harm. Despite its reputation as a source of nectar for honeybees, scientific studies of this plant have shown that it causes declines in riverside plant and insect diversity. This rapidly growing annual plant also outcompetes other plants. Each autumn Himalayan balsam dies back leaving riverbanks bare in winter. Bare riverside soil is much more vulnerable to erosion after heavy rain, and the washed away soil causes major damage downstream and kills wildlife. We can all play our part to reduce the spread of invasive species:

· Never throw away garden waste in the countryside – compost and recycle.

· Do not plant spare garden plants along roadsides or nearby woods, as this can spread invasive plants and damage or destroy what is already there.

· Always compost excess oxygenating plants from your pond and do not put them in a pond nearby. Many oxygenating aquatic plants are highly invasive and may spread pests and diseases.

3. Ever heard what sounds like an over-excited bee buzzing in

your garden? This is often the sound of doom: a bee has just been caught in a

spider’s web. Bees often meet this fate in my porch where, to us, harmless

false widow spiders (Steatoda) lurk. The bees are attracted by a 2 metre

high pelargonium growing by the back door – I live in a mild part of the

country! More happily, it is also the sound of buzz pollination (also known as

sonication). This high-pitch, intense buzzing sound is produced by bumblebees

(honeybees cannot do it) as a way of releasing pollen from certain types of

flower. On visiting a flower, bumblebees tense their flight muscles to produce

an intense vibration that shakes the pollen loose. Why do this? Well, it is

because the plants are in control. Producing pollen ‘costs’ the plant in

resources (just like bringing up children) and the plant protects its

investment by ensuring that the pollen is made available to the best

pollinator, in this case bumblebees. Many types of plants depend upon

bumblebees to spread their pollen in this way. In our gardens and allotments,

members of the potato family, such as tomato, aubergine, and peppers, all need

their services. That is why it is important to leave the greenhouse door open

at flowering time. I have also seen, and heard, bumblebees doing this with

anemones, borage, poppies, roses and many other garden and wild plants.

4. No one likes getting stung by stinging nettles (Urtica dioica). While they hurt a little, their power is nothing compared to the mind bending pain of the Australian gympie-gympie (Dendrocnide) a relative of our ‘stinger’ that grows to the size of a tree. The sting of a gympie-gympie is so painful that there is a story of a horse throwing itself off a cliff to escape the pain! Our relatively benign plant evolved its sting to protect its nutritious leaves from grazing. In areas where grazing pressure is low, especially in marshes, there is a form called the fen nettle, which is almost stingless. The scientific name for fen nettle is galeopsifolia, which means it has leaves that look like hemp-nettles (Galeopsis), plants that are related to dead-nettles. Neither hemp-nettles, nor dead-nettles are related to the plant family Urticaceae to which our ‘stingers’ and the gympie-gympie belong; they are related to mint, in the family Lamiaceae. Stinging nettles are well-known as a food plant for caterpillars. They are also excellent indicators of rich soil, which is one of the reasons that nettles are often found in gardens and allotments. Alongside the big and burly stinging nettle, you may also come across the small nettle (Urtica urens). This annual plant has quite a powerful sting compared to its larger perennial relative. Small nettle is an archaeophyte. This means it is an ancient introduction to Britain, unlike the almost stingless Mediterranean nettle (Urtica membranacea) which is a neophyte. The first time Mediterranean nettle was seen wild in this country was in 2006, hence ‘neo’ (new) and ‘phyte’ (plant).

4. No one likes getting stung by stinging nettles (Urtica dioica). While they hurt a little, their power is nothing compared to the mind bending pain of the Australian gympie-gympie (Dendrocnide) a relative of our ‘stinger’ that grows to the size of a tree. The sting of a gympie-gympie is so painful that there is a story of a horse throwing itself off a cliff to escape the pain! Our relatively benign plant evolved its sting to protect its nutritious leaves from grazing. In areas where grazing pressure is low, especially in marshes, there is a form called the fen nettle, which is almost stingless. The scientific name for fen nettle is galeopsifolia, which means it has leaves that look like hemp-nettles (Galeopsis), plants that are related to dead-nettles. Neither hemp-nettles, nor dead-nettles are related to the plant family Urticaceae to which our ‘stingers’ and the gympie-gympie belong; they are related to mint, in the family Lamiaceae. Stinging nettles are well-known as a food plant for caterpillars. They are also excellent indicators of rich soil, which is one of the reasons that nettles are often found in gardens and allotments. Alongside the big and burly stinging nettle, you may also come across the small nettle (Urtica urens). This annual plant has quite a powerful sting compared to its larger perennial relative. Small nettle is an archaeophyte. This means it is an ancient introduction to Britain, unlike the almost stingless Mediterranean nettle (Urtica membranacea) which is a neophyte. The first time Mediterranean nettle was seen wild in this country was in 2006, hence ‘neo’ (new) and ‘phyte’ (plant).

© Mark Spencer, 2021

Becoming

artist books and podcastsCamilla Nelson

November 2020

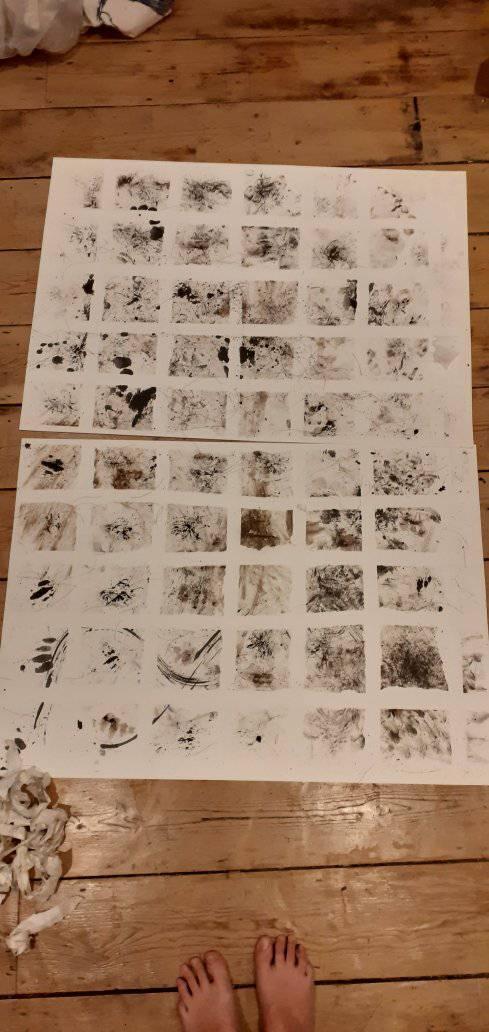

BECOMING is a creative enquiry into the relationship of human and nonhuman organisms expressed through the medium of poetry, theory, soundart, fine art and performance. This project investigates what it is to BE fungus, plant, insect, bird and animal in a shamanistic effort to better explore and integrate these different ways of being into our human selves.

At UnderGROWTH’s invitation BECOMING developed into a number of performative experiments into becoming insect, plant, bird and animal through movement and mark-making. The result was a series of original artworks, poems and creative prompts that were handbound into sixty-six booklets and accompanying artworks for delivery across Coventry via The Pod. Recipients are encouraged to share their prompts, artworks and poetry to create a fungal network - a wood wide web - of creative resources across Coventry to better support and integrate these plural ways of becoming.

At UnderGROWTH’s invitation BECOMING developed into a number of performative experiments into becoming insect, plant, bird and animal through movement and mark-making. The result was a series of original artworks, poems and creative prompts that were handbound into sixty-six booklets and accompanying artworks for delivery across Coventry via The Pod. Recipients are encouraged to share their prompts, artworks and poetry to create a fungal network - a wood wide web - of creative resources across Coventry to better support and integrate these plural ways of becoming.

Day 1 of remote underGROWTH residency: bodily BECOMING FUNGUS

Imagining limb slop into earth. Feeling the neural connections growing between mycelial particles underground. Imagining the uptake of nutrients from soil, the sharing of water and information along these fine tendrilling pathways to become mushroom. Face and eyeballs full of spores. Finally released into the room. Limb slop back into soil. Begin again.

This exercise was one I learnt from Other Spaces on a residency at Secret Hotel with Minja Mertanen and Lauri Kontula, hosted by Christine Fentz. Inhabiting this "other space" reminded me of why I live this life. Working creatively, for me, is not about making stuff so much as inhabiting this mode of embodied imagining. Lovely to remember this in a time when arts practices have had to become more isolationist.

Day 2 of underGROWTH remote residency: BECOMING INSECT

I find that I do not like using my eyelashes to examine odd things on the floor. I do not like pressing my face into cold damp earth. I do not like trying to move my whole body over the floor with no help from my limbs. There is much I do not like about becoming insect. But.. I find moving my arms, hands, fingers through soil on paper brings much joy.

Day 3 of remote underGROWTH residency: BECOMING PLANT

Being is a way of knowing. Celery first, then dandelion. Make a sound with a plant. Make a sound like a plant. Move with a plant. Move like a plant. Make a mark with a plant. Make a mark like a plant.

"a fluttering intake of breath / percussive feather tap / fingers triangulate chlorophyl fractals.."

Day 4 of remote underGROWTH residency: BECOMING BIRD

Listen: where do they call? how do they call? Watch: where do they move? how do they move?

quack foot feather

find a song and pull it out of you

befuddle the water with a wading unwebbed footstep

Day 5 of remote underGROWTH residency: BECOMING ANIMAL Taking the prompt from Scott Thurston's reflection on his work with Helen Poyner, I started at floor level: spine loose & flexible, legs functioning independently, sliding over the floor. Moving into animal: on all fours, focussing on the deliberate placement of limbs, paws, pads, with an awareness of the structure of the body.

Scratching, scratching. Disatisfied resistance. Mourning a sculptural sense of smell. Frenetic digging. Ineffective attempt to break ground. Scapula proud. Tear it apart. Try to revive a sensual amnesia. I am grieving the forgotten animal. Locked into the sensate stupidity of being human.

Nail scurf. Nose lick. Breath hog. Mane antagonist.

Day 4 of remote underGROWTH residency: BECOMING BIRD

Listen: where do they call? how do they call? Watch: where do they move? how do they move?

quack foot feather

find a song and pull it out of you

befuddle the water with a wading unwebbed footstep

Day 5 of remote underGROWTH residency: BECOMING ANIMAL Taking the prompt from Scott Thurston's reflection on his work with Helen Poyner, I started at floor level: spine loose & flexible, legs functioning independently, sliding over the floor. Moving into animal: on all fours, focussing on the deliberate placement of limbs, paws, pads, with an awareness of the structure of the body.

Scratching, scratching. Disatisfied resistance. Mourning a sculptural sense of smell. Frenetic digging. Ineffective attempt to break ground. Scapula proud. Tear it apart. Try to revive a sensual amnesia. I am grieving the forgotten animal. Locked into the sensate stupidity of being human.

Nail scurf. Nose lick. Breath hog. Mane antagonist.

image courtesy of the artist

image courtesy of the artist